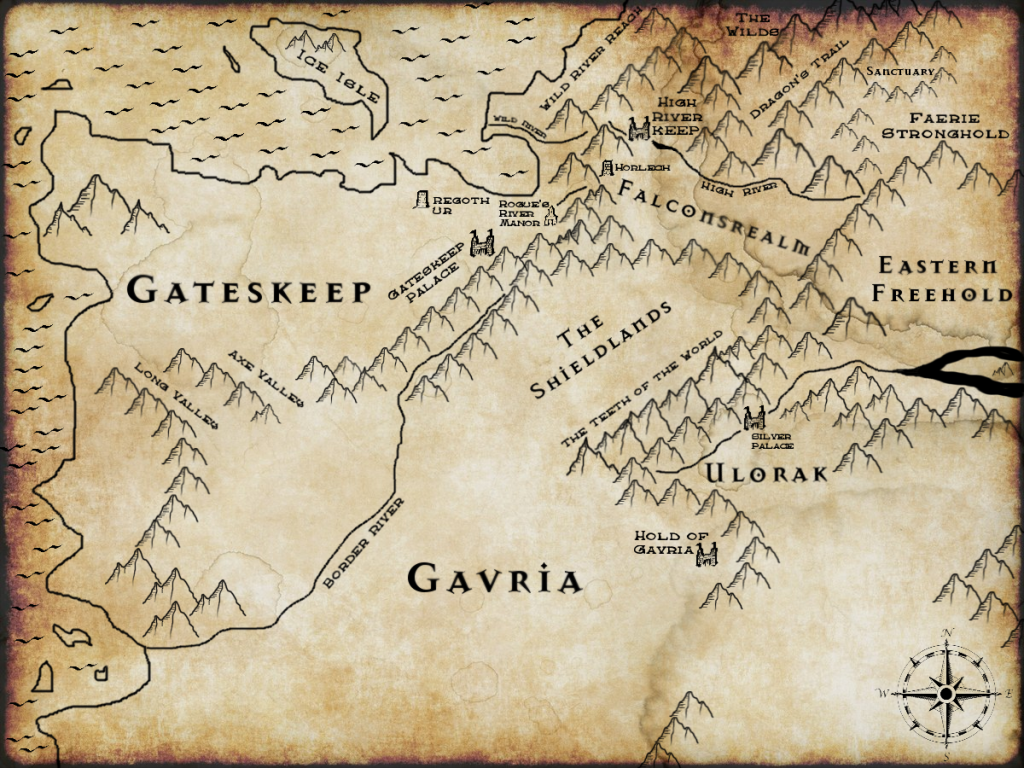

The map of the world where Dragon’s Trail and subsequent books take place.

The map of the world where Dragon’s Trail and subsequent books take place.The second book deals with an uprising in the Shieldlands, (spoiler alert) and I’m going to have a bitch of a time working that out on paper because the whole area is essentially a Jackson Pollock painting of petty fiefdoms. But that’s next winter’s problem.

Yes, there are a lot of mountains.

I gave the planet a huge moon — I still haven’t decided if the planet is a moon orbiting something bigger, or a binary planetoid; I worked the math both ways. But the tidal forces tear the hell out of the planet, making jagged, Patagonia-esque mountain ranges.

|

| Really no better way to blow a jaded character’s mind than to give him a couple of days believing he’s in a reality show, then have the clouds part one night to reveal something like this. “So, I take it my agent’s not coming, then.” |

Also, the tides are huge and the oceans have enormous waves, making them nearly un-navigable. Innavigable? There should be a word for that. There probably is. What I’m saying is, they’re really tough to navige.

Medieval Stasis is something that most fantasy writers can’t live without. The trick is justifying it, at least to the point of suspension of disbelief.

The moon’s size and proximity means the world is prone to massive earthquakes, and every thousand years or so it goes through what they call The Cataclysm (I’ve decided that they suck at naming stuff), which wipes out large swaths of civilization and they have to start over again.

The moon tied the whole thing together and led not only to the easy realization for the characters that they hadn’t gone back in time, but from a world-builder’s perspective, the moon’s power led to the concept of a civilization in a constant state of rebuilding, with eons of lost history showing up in bits and pieces. Look for warriors showing up to battle in armor that’s been handed down for a thousand years but is still three hundred years ahead of current tech.

I went Vendel-Age / Late Viking on the technology to keep it simple; things moved so fast in the early Middle Ages that it was really tough to nail down an analogous time period in which the world could remain in stasis, but the end of the Vendel Age saw a degree of technical homogeneity across a good swath of the world. That was also a time when steel was about as valuable as gold and warriors were still wearing armor handed down from Roman invaders six hundred years before. Sometimes things just work themselves out.

I trained in desert warfare in the Horn of Africa, and the field exercises gave me a whole new appreciation for the degree to which earthquakes and volcanoes could completely screw over millions of people and keep them scrabbling about making do with whatever technology they could keep their hands on. I now know more about camels and vintage rifles than any modern soldier should. But I digress.

I went left-justified on the map. I don’t know why; everyone does, it turns out, so much so that it has its own trope. Gavria turns to a shithole to the south, sparsely populated and very tough to traverse, and the Eastern Freehold is hostile and weird and the mountains are a bitch to get over, plus they speak a different language, so nobody worth knowing ever goes there or comes from there.

Ulorak is basically a high plain, originally inhabited by refugees from the Eastern Freehold, now a trading crossroads.

The forests are too wild to traverse safely. Big chunks of Gateskeep — so named because, notice, there are only two ways in from the south: Axe Valley and Long Valley, hence, two gates — are still unexplored or at least unmapped.

Which brings up another point: have you ever seen a map drawn in the Dark Ages?

Me, neither.

I don’t think that, given a Planet England trope, they’d have a really great idea of where anything was other than, “forests over here, big mountains there, kinda small mountains over there.” Which should make military maneuvers a laugh a minute, lacking detailed terrain considerations.

With geographic features sufficing for hard borders, there are plenty of opportunities for snarkiness and small wars all over the place, which keeps the weekends interesting.