So. Armor.

Because if I get asked “What kind of armor would my character wear?” one more time I’m going to beat my brains in on my laptop keyboard. I’m going to talk about medieval European armor. Mostly. All this tech that we’re about to discuss can be transposed across pretty much any fantasy society.

“Most fantasy armor falls between these two extremes. Does that help?”

We’re going to talk about what armor is, what it isn’t, and why it is the way it is. Take the fundamentals from this and go nuts. Let me know what you come up with. You don’t have to be historically accurate–and if you’re using magic, you don’t even have to roll with the physics involved in this post–but your armor should at least make sense, and making armor make sense is really the best I can hope for, here.

A good friend of mine once told me: armor is not a thing; it is a process. Warriors wore as much as they could afford, or as much as they thought they needed. Which was usually as much as they could afford, and sometimes more. They were always working on their armor, tweaking it, adding to it, and attempting to improve it.

Fantasy writing is research. There are entire books written on armor. There’s also a ton of information on the Internet but if you get your information from anime or gaming enthusiasts, you’re going to be wrong. A lot. So let’s take a few minutes and set some things straight.

Most importantly, armor was composed of several layers.

The first layer, and the most basic armor, is/was the linen jack.

Drafty, but effective from the knees up.

The linen jack wasn’t bad armor. The layers of linen would stop some slashing weapons. If it was padded or quilted, it would protect against some of the incidental damage that wears you down in a fight: the bumps and bruises and little pain-in-the-ass nicks that stack up quickly and throw you off your game. It was also, more or less, the underlayment for other types of armor.

Later, the linen jack became a gambeson:

Over the jack went a tabard of leather, or sometimes felted wool.

Some guys stopped here.

Indeed, some should go no further.

You can get creative with this. On movie sets, stunt players who have to really take a beating in medieval armor will use professional bull-riding vests as a base layer. Padded motocross jackets also work very well. It’s all the same principle.

Over the tabard you’d throw a shirt of mail, if you had one.

And assuming you hadn’t eaten it for breakfast.

The key, though, was having the tabard and the jack under the mail. Again: layers. You will read — and probably have already read — that mail doesn’t disperse force from blunt trauma. Nothing could be further from the truth. Mail actually is designed to disperse force from blunt trauma.

When you drive a blow into a shirt of mail, the mail ripples outward, like a stone thrown into a pond. As the ripples get larger, progressively more force is needed to lift each expanding circle of rings. It dissipates the blow very well. The SCA wouldn’t allow it if it didn’t provide some degree of impact protection. They fight with wooden weapons at full-speed. It’s nothing but blunt trauma.

Mail, over a stiff leather tabard, over padding, is pretty good armor. A shirt of interlocking metal rings over some kind of padding was the primary method of saving your ass in a war for about two thousand years, maybe longer, worldwide. The earliest mail we’ve found so far dates back to 300 B.C. It’s possible that bronze and even copper mail was used long before that. Don’t tell me it didn’t work. If it didn’t work, we’d have used something else all that time.

Mail also provided excellent protection against thrusting weapons, functioning much the same way as ceramic plates in modern body armor. The tip of the weapon would have to break several interlocked rings, which robbed the thrust of a great deal of force. It wasn’t until the widespread adoption of weapons specifically designed to defeat mail — heavy swords like the gran espee de guerre, specialized axes and hammers, and anything resembling a pickaxe, among other nasty things — that mail really needed to be augmented.

A shirt of iron mail (yes, iron; stick with me) weighed 20-30 lbs. Until the 1300’s, most knights and professional soldiers — according to the historical record — wore layers of mail. A mail shirt, mail leggings, a mail gorget and mantle, and a mail hood under their helmet. Mail was that good. Mail was awesome.

Mail was riveted. Unless you were insane. This is why it was made of iron. The rings were punched from a sheet of metal, and it is REALLY hard to punch steel rings. It is way harder to make steel wire than iron wire with medieval technology. It is harder, still, to nip, flatten, drill, and pin steel wire and rings with medieval technology. Iron is malleable and ductile. Steel is not.

Riveted mail looks like this:

Alternating punched (flat, sheet metal) and riveted (round, wire) rings.

If you don’t rivet mail — if you simply butt ends of wire together the way LARP’ers and SCA jocks do — this happens when you hit it with something heavy and/or sharp:

It’s all fun and games until somebody loses a face.

These plates are made of high-impact plastic. Early coats of plates would use plates of thick leather, and later, cuir bouilli.

The plates in a coat of plates could have been iron, cuir bouilli, or even bone.

Cuir bouilli — boiled leather — was interesting stuff. It was medieval plastic. When vegetable-tanned leather is submerged in boiling water, the fixed tannin aggregates in the leather begin to melt. Leave it in hot water long enough, and the tannin aggregates create a resin that redistributes itself throughout the fibers of the leather. Upon cooling, the resin-soaked fibers become, for all intents and purposes, a polymer: malleable when warm, and cooling to a hardness that rivals high-impact plastics today. A curved surface of polymerized leather will turn a blade.

You can do some really cool stuff with cuir bouilli. It wasn’t expensive, it was easy to work with, and it was really damned effective. I like to think that it was used a lot more than we realize, because it would rot away over the centuries so now there’s nothing left.

This is “elf” LARP armor but it’s fairly easily done. This was technologically possible during the Migration Era, and even further back. You need a tanned hide, and boiling water. If you had a carved wooden mannequin, you could mass-produce these. Put them over mail, and you’re rockin’ some serious protection.

Except that he built this lamellar backwards and upside down. An overhand blow from a right-handed person will only intersect one thickness of plates. Live and learn. Or, not so much, really.

It weighs sixty pounds, but you could drop a piano on this guy and he’d laugh at you.

Back to cuir bouilli. Here’s an articulated cuir bouilli harness; again, throw a full suit of this over mail and you could kick some serious ass. It’s basically plate armor.

This is a mail hauberk and hooded mail mantle, with spaulders, a lamellar jacket, and bracers all made from cuir bouilli. It would make sense to me that armor like this existed, primarily because it’s functional, tough, modular, fairly low-tech, and it looks awesome.

Looking awesome was important. This has not changed throughout the history of warfare.

A padded jack, over mail, which is worn over a padded jack. Sensing a theme, yet?

This next picture is a coat of plates (under a tabard), over mail. This armor predates his sword by about 200 years but hey, Hollywood.

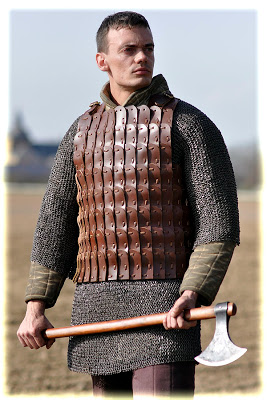

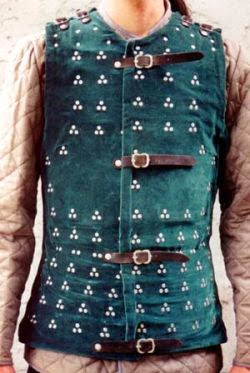

Coats of plates became brigandine in the late 1300’s. Again, small pieces of good iron, or even steel if you were really a baller.

Actual Italian brigandine, 14th-Century. This is the inside.

I wouldn’t wear anything made of velvet to any event as blood-splattery

as a medieval battle. I wouldn’t even eat spaghetti in this. Just sayin’.

And so on.

Every soldier would put together what he could afford, depending on personal taste, the next mission, and the local technology. Again: armor was not a thing. It was a process.

That brings us to odds and ends.

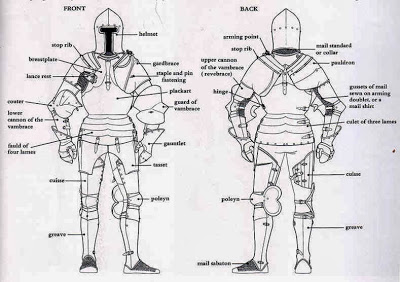

First off, shoulderpieces. Pauldrons and spaulders. These were important, because your shoulders get hit a lot. This brought about a new era in armor concepts, as the purpose of pauldrons, cops, and helmets wasn’t to stop a weapon but to redirect it by glancing it off a hard, curved surface.

As Europe learned mathematics and then applied it (which is physics, and applied physics is engineering), Europeans started building armor with compound curves.

The third image returned by Google for “compound curves.” If I hadn’t put it here, you’d have seen it anyway.

A compound curve is two or more circular arcs of differing radii, joined tangentially without reversal of curvature. What does this mean? It means that if you drive an edge into a compound curve, you have no idea what direction it will go. Your sword or axe will skip off like a SuperBall. There’s also a good chance that, if you drive a sword directly into a compound curve, the force of the blow will be returned to the weapon and it will either sting your hand, or–if the sword’s steel was bullshit–the blade will snap or bend.

Pictured: Science.

The reason that real armor doesn’t have spikes, but fantasy armor does, is that a spike will redirect a weapon’s effort into the armor, bisecting the angle between the spike and the plate and cutting into the armor.

“Nice spikes, numbnuts. You wanna just give up now?”

The presence of spikes on armor is one of the first signs that an author doesn’t know what the hell they’re talking about.

So let’s start with the basics. Again.

I’m still fuzzy on the whole “spaulders” vs. “pauldrons” thing, but the way I understand it, “spaulders” were stand-alone shoulderpieces, whereas “pauldrons” were integrated with other pieces of armor. “Grand pauldrons” were larger, covering the entire shoulder. Scales or plates that covered the upper arm, attached to the shoulderpiece, were called lames (“la-MAYS”).

Simple cuir bouilli spaulders with lames.

Grand pauldrons. The shoulder flare may or may not be authentic. I say yes, because it looks badass. It may serve the same function as a spike, however, completely undoing the benefits of the compound curves.

A pauldron with compound curves and lames. Note the rawhide lacing. The rawhide lace might either be part of the arming jacket, used to keep the pauldron in place, or it functions to attach the pauldron to a gorget.

You could put a chest / shoulder rig over mail and call it good. It would be better over lamellar or a coat of plates. My main character wears a mantle and grand pauldrons, over a coat of plates, over mail. Because he might need to survive an axe fight.

For the lower arms, you’d want an elbow piece of some type, and something for the forearm. For the elbow, you would use a cop:

Which could be tied into a vambrace of some type:

And this is realy cool — bazubands, a Persian solution to the whole problem. Combination elbow and forearm protection.

My main character also wears these. Because awesome.

Somebody sooner or later decided to attach the elbow to a rerebrace (bicep/tricep piece) and vambrace (forearm guard):

And he probably got mad babes. “Digging your compound curves, milady.”

And eventually somebody got the idea to just articulate the whole thing out of metal:

And carried the concept over for the legs:

Resulting in this:

This, you’ll notice, is one step away from the full man-at-arms harness that we’re all familiar with from museums, the Tower of London, Stately Wayne Manor, and your mother-in-law’s house. Really he’s just missing a breastplate. This is what AD&D calls “plate mail,” which many historians claim didn’t exist as an actual thing, only it actually kinda really did and was probably very common. There’s just no name for it.

It wouldn’t be unusual throughout the Dark and Middle Ages — and you’ll see this throughout Dragon’s Trail — to see a soldier in a shirt of mail with a haphazard shoulder and chest harness of iron and cuir bouilli, with, say, metal splinted greaves and leather Persian-style bazubands, and an antique helmet that had been handed down through his family for two hundred years. Parts of his armor would be shiny and new and reflect the local artisans; parts would be relics carried home from wars long-won or long-lost.

The kind of armor that we see most commonly in fantasy —

There will be a quiz.

— didn’t exist for most of the Middle Ages, though most fantasy heroes seem to have this stuff lying around somewhere (or worse, they go to Armorer’s Alley in the local town and buy it). This is a man-at-arms harness, what people call “full plate” armor. It was extremely expensive, took years to build, and was the mark of exceptional wealth, on par with having a private jet today.

Pictured: pimpin’.

But look at it: it’s basically all the parts we’ve listed above, connected, and worn over mail, over a tabard, over a padded linen jack. We are standing on the shoulders of giants.

This suit, above, is from the late 1400’s, about as elaborate as it gets. This armor didn’t exist for very long, because after a couple hundred years of this bullshit, generals threw up their hands and started handing out guns.

Most metal armor was iron. The technology did not exist to produce large sheets of homogenous steel — steel is iron mixed with carbon — until the invention of the blast furnace, which helped kick off the Industrial Revolution well after all this had already happened.Steel is a Goldilocks zone of carbonization in iron. When you add carbon to iron, it alters the properties of iron. If you add too much carbon, you get cast-iron, which is brittle; too little, and you have wrought-iron, which is bendy. Steel is the sweet spot between bendy and brittle. Steel is hard, and yet forgiving. And really, really tough to get exactly right in a pre-industrial environment. (A major plot point in Dragon’s Trail hinges on Viking-era steelmaking technology and the resultant impact of the ore trade on military readiness.)

Most pre-industrial steel was shear steel, which is iron bars baked in charcoal and then heated up and folded with a hammer (forge-welded) to basically stir the charcoal (carbon) into the iron. It is painstaking, and it would have been staggeringly difficult and expensive to make shear steel in pieces big enough and consistent enough to use for, say, grand pauldrons, great helmets, and breastplates.

I know that every hero in every book and every fairy tale has steel armor. I know. Do me a favor, though: watch how much work goes into forging enough steel to make one small sword or tool.

How steel was made. Seriously.

And this is using a modern furnace. Now imagine the amount of work involved in making a steel man-at-arms harness. It was done, don’t get me wrong. But the suits of full harness that survive today include some suits of steel armor because they belonged to people who, at the time, were comparatively richer than most people who have ever lived. Those suits have survived because they were carefully oiled and dusted for hundreds of years. They were priceless. Imagine a Gulfstream G650 plated in solid gold. That’s a steel harness.

Weapons were made from steel because armor was made from iron. We’ll cover that in detail in another post.

Nowadays we take steel for granted. I was recently reading a fantasy novel–and I hope the author is reading this–where the author thought that steel was an ore, that it came out of the ground ready to be heated and formed. Maybe in some worlds this happens, but I’d hate to see what kind of weapons they would come up with. Also, if you have so much easily-made steel that every knight has a full suit of steel harness, then you have enough steel for doors, reinforced castle walls (and beams for super-high towers), battering rams, and so on. You now have tremendous worldbuilding problems to solve. Plus, your knightly weapons aren’t going to work; hit steel armor with a steel sword and nothing happens. Steel bites iron they way a diamond bites glass, which is how a hand weapon transfers its force to armor and dents it enough to eventually compromise it (see above about compound curves). Your warfighting will look nothing like the warfighting that you’d expect in that time period. You’ll need to invent it.

Moving on. Each full harness was custom-made and would only fit one person. It weighed anywhere from 40 to 60 lbs, including the mail that went under it. That weight was exceptionally well distributed, and is less than my current combat load in the Army, which is 76 lbs. including armor, weapons, ammo, water, and a half-pound bag of sour Skittles.

There’s a misconception that armor weighed hundreds of pounds and left a man as helpless as Ralphie’s little brother in his snowsuit from A Christmas Story.

A quick aside: the suit of armor in the video above coexisted in the same time and the same areas with brigandine. Why? Because brigandine was a hell of a lot cheaper, and much easier to fix, and protected almost as well.

Also, on the subject of maneuverability, this:

Tell me again how armor was so cumbersome that you couldn’t fight in it. I wasn’t listening.

Whether your armor is a full harness or an amalgamation of pieces, it’s heavy as hell. But that doesn’t matter, because weight is not a concern. You can fight in it, and it keeps you alive. Those are the two factors that determine whether or not armor is “good.”

Armor is heavy. It sucks. But it works. That’s why soldiers wear it, even today. I’ve said this before: if I knew my armor wouldn’t work, I’d go back to central issue and turn it in. Because fuck armor. Seriously. This sentiment–fuck armor–has not changed over the millennia. I believe with all my heart that burly Vendel-age warriors shucked off their mail with a groan at the end of the day and wanted to hurl it across the room with a snarl the same way that we want to throw and kick our IOTV’s today.

But anybody who fights for a living — and this includes your fictional heroes — will want as much protection as they can get; whatever they can afford and whatever they can transport to the battle site, whether they wear it, pack it on a second horse, or have a wizard teleport it to the mouth of the dragon’s lair along with a team of valets who will work on them like a pit crew once they get there. They will want it as light and comfortable as possible and they won’t wear any more than they think they have to, but they’ll wear as much as they can get away with. They might — might — forgo a degree of protection for convenience, but speaking as a professional soldier, myself, I don’t know anyone who would do this knowing that enemy contact was certain or even likely. Sure as hell not if they’re going off to fight The Big Boss, which it seems is the crux of every high fantasy novel.

My first thought, if I receive a mission with expected enemy contact, isn’t “Boy, my armor’s really gonna slow me down.” My first thought is “Now, where did I put all those extra pieces of body armor?” Followed by “I hope I’m on the 240 Bravo,” and “I wonder how many grenades I can fit in this pouch.”

I don’t care if it adds another 30 lbs. to my load-out. If there are going to be badguys trying to put holes in me, I want every pound of armor that I can scrape together, plus whatever weaponry comes closest to being “excessively injurious or having indiscriminate effects” according to the laws of war without technically going over the line. I’d carry a minigun if I could just get my minions to schlep the electrics and ammo around behind me. I’m convinced that this mindset has been pretty much consistent throughout the history of human warfare.

Even if the armor is heavy, even if it’s ugly, even if it’s hot and sweaty and it causes blisters and ringworm and it smells like an Uruk-Hai’s thong, your heroes will use as much of it as they can, along with great big honkin’ shields and massive helmets and the biggest weapons that they can wield effectively, if they have any instinct for self-preservation.

To recap:

NO.

YES.

YES, BUT NO.

YES.

Warriors use armor because it works. Make sure your hero’s does.

This was super-educational. I appreciate you taking the time to write it up.

And it’s turning everything I ‘learned’ in my table-top games completely on its head. Especially how effective cuir bouilli.

Question if you don’t mind: I’ve been told Dark Age/Medieval raiders didn’t wear leather armor because the seawater air would mess it up. Would cuir bouilli stand up better to that erosion?

I appreciate you sharing your knowledge.

Hey, Nathan. Thanks for your comment. I’m glad you found it useful.

I don’t have any information on seawater air destroying leather armor. I had cuir bouilli plates that I did destructive testing with many years back, in Seattle, and even when wet from rain they held up just fine. I believe–and can’t prove, I’ll admit–that cuir bouilli was used a lot more commonly than we think; it just didn’t survive because it biodegrades. It’s cheap, simple to make, and effective. I can’t imagine warriors not using it whenever possible.

Thank you for taking the time to answer my question. I look forward to your next release this September.

This is awesome! I want more like this. How about a similar work on weapons and the rigs used to carry them?