Part One: What It Is and What It Ain’t

Disclaimer: There is no “correct” way to write a novel. I keep getting asked, “How did you sell so many books?” The Short and Scrappy Guide to Novel Writing reflects what has worked for me.

I’ve been asked quite a bit lately to do some writing about writing, so here we go.

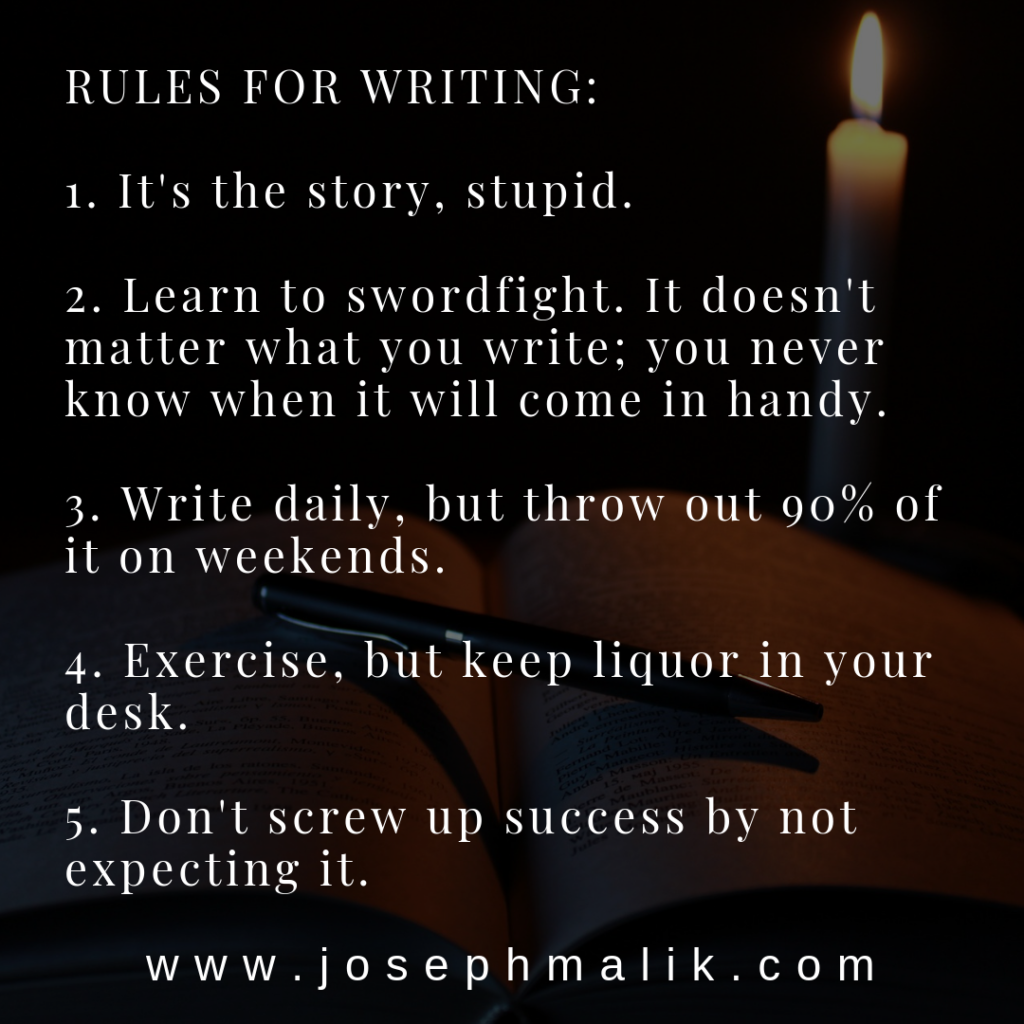

First things first: my five rules.

With this out of the way, let’s just start at the very beginning.

I want to start by defining what a novel is. Truth told, I want to redefine it, at least for the purposes of the next couple of blog posts, because we’re going to need to drill down on some core writing concepts that will help you sell books. A lot of what’s being self-published today doesn’t do the one basic thing a book needs to do to move big numbers, so we’re going to use the presence of that thing to want to delineate between the books that sell for years and the other 10,000 books self-published every week that move five copies at 99 cents and sink under the waterfall.

Ask anybody in the indie writing space these days to define a novel, and they’ll tell you a novel is any book over a certain word count. That count varies—40,000, 50,000, 60,000—depending on whose line of bullshit they’re buying.

I say bullshit, because . . . well, because it’s bullshit.

Okay, look. Technically, the dictionary definition of a novel is a >40,000 word book. Fine. Swell.

. . . BUT . . .

The dictionary also says irregardless is a word, and I refuse to accept that.

There are plenty of novels under 40,000 words.

Julian Barnes’ The Sense of an Ending was 163 pages—just under 40k words—and it won the Man Booker Prize. Yuri Herrera’s Signs Preceding the End of the World is 128 pages, ~30K words, if you read the Dillman translation.

“But those aren’t fantasy novels.”

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe was 38K.

“But, but, muh science fiction!”

Asimov’s The End of Eternity was just over 25K.

So, yeah. Bullshit.

So, how is a 25,000-word book considered a novel?

Glad you asked.

To answer this, we have to go back in time a bit; to the 18th Century. The mid-1700’s. Robinson Crusoe was arguably the first English novel, published in 1721. (Keep that in your hat for trivia night if bars ever open up again.)

Novels emerged when the primary form of literature was the romance. (“Romance,” as it applied at the time that novels came about, didn’t refer to ripped bodices and sweaty bodies making squishing noises in a steaming, throbbing mass. “Romance” referred to romantic prose: old-school adventure stories of heroes and knights and chivalrous feats of valor and whatever.) The defining feature of the novel was—and, I will argue until my dying breath, still is—that a novel is a fictional narrative reflecting on social, political and personal realities through the employment of literary devices.

Novels were also different from allegories, the other big literature at the time, in which the characters and events all stood for something else. Novels presented realistic stories in which the characters and events stood only for themselves, but, in so doing, they reflected on social, political, and personal realities. No heroes, no kings, no dragons. Just people, doing stuff, getting in adventures, and learning about the world and themselves as they did so.

However, as novels developed, allegories died out. Novels incorporated allegory, along with other literary devices, many borrowed from poetry—exposition, foreshadowing, symbolism, metaphor, irony, all that stuff that some of us snoozed through in third-year theory—to develop a type of story that tells an entire other story without actually saying it out loud.

With me so far?

No? Kinda?

It’s cool. We’ll get there.

STORIES VS. NOVELS

A story contains eight elements: theme, setting, character, plot, conflict, point of view, tone, and style.

The literary devices we talked about up there—exposition, foreshadowing, symbolism, allegory, metaphor, irony, and the probably hundred others on the linked site—became the differences between novels and romances as novels developed. Romances were stories. They were one-dimensional. They told a story, and the story was the story, and that was it.

Novels, as they developed, became radical departures from romantic stories. As we got into the mid- to late-1700’s, novels employed literary devices more and more, eventually creating an unspoken second story that resided within the text on the page.

This is important, because the words in a novel meant more than their concrete definitions. That unspoken meaning is subtext. Subtext was unique to novels, and it’s what, to me, separates a novel from a novel-length story. This is where we’re going to redefine the novel as I talk about how to write one that will sell.

Novels were initially seen as akin to poetry: flowery, superficial, even vacuous, and it’s one of the reasons novels were pooh-poohed in the early days. They weren’t considered “serious” literature until later.

Once people caught on to the layers of meaning hidden in the flowery words, some novels were considered scandalous for their commentary. That’s when novels started to be cool.

By the mid-1800’s, analyzing novels became an intellectual pastime: “Ah, yes, I’ve read that novel. What the author really meant, you see, was . . .” and so on, arguing over brandy late into the evening, and once it became the hip thing to do, well, here we are now.

This difference between novels and stories is, I will argue, still true today. If you have a 60,000-word book that has no subtext, i.e. it’s written entirely concretely (looking at you, PNR, I see you hiding behind the couch) I will argue that you don’t have a novel, you have a novel-length story. Which is great, but it’s not the same thing.

I know, I know. Pulp novels, detective novels, romance novels, cozy mystery novels, BBW BDSM Biker Billionaire Bad-Boy Babysitter Alpha Shifter Reverse-Harem Erotica novels, they’re all “novels.” It’s right there in the name.

I get it. I’m not talking about those, now.

Actually, I could be, because there are books in all those genres that incorporate subtext, albeit perhaps not world-changing discourse on the human condition. And that’s fine, too. Not all subtext has to be particularly insightful nor consequential to the betterment of humanity. Your subtext can be “peanut butter is a great food.” But you have to have it, if you want to have a novel that’s going to sell. Really sell. Subtext is something you bring to the story that no one else can. It’s what will set your book apart from the other books that, on their surface, may resemble it. Being set apart is the first step to making sales.

So, for our purposes, subtext defines a novel. Screw your wordcounts. The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, at 38,000 words, has subtext out the ass.

And subtext sells.

More on that in Part II. Buckle up.